Filter

Associated Lab

- Ahrens Lab (2) Apply Ahrens Lab filter

- Aso Lab (1) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Baker Lab (1) Apply Baker Lab filter

- Branson Lab (1) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Druckmann Lab (3) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Harris Lab (3) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (9) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Hess Lab (1) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Remove Jayaraman Lab filter Jayaraman Lab

- Ji Lab (1) Apply Ji Lab filter

- Karpova Lab (1) Apply Karpova Lab filter

- Looger Lab (10) Apply Looger Lab filter

- Podgorski Lab (1) Apply Podgorski Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (2) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Romani Lab (5) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (6) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Saalfeld Lab (1) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Scheffer Lab (1) Apply Scheffer Lab filter

- Schreiter Lab (9) Apply Schreiter Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (9) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

- Zlatic Lab (1) Apply Zlatic Lab filter

Associated Project Team

Publication Date

- 2025 (1) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (3) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (1) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (3) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (1) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (4) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (4) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (3) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (4) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (3) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (4) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (1) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (3) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (2) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (2) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (2) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (2) Apply 2009 filter

- 2007 (1) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (1) Apply 2006 filter

- 2003 (1) Apply 2003 filter

Type of Publication

46 Publications

Showing 31-40 of 46 resultsThe identification of active neurons and circuits in vivo is a fundamental challenge in understanding the neural basis of behavior. Genetically encoded calcium (Ca(2+)) indicators (GECIs) enable quantitative monitoring of cellular-resolution activity during behavior. However, such indicators require online monitoring within a limited field of view. Alternatively, post hoc staining of immediate early genes (IEGs) indicates highly active cells within the entire brain, albeit with poor temporal resolution. We designed a fluorescent sensor, CaMPARI, that combines the genetic targetability and quantitative link to neural activity of GECIs with the permanent, large-scale labeling of IEGs, allowing a temporally precise "activity snapshot" of a large tissue volume. CaMPARI undergoes efficient and irreversible green-to-red conversion only when elevated intracellular Ca(2+) and experimenter-controlled illumination coincide. We demonstrate the utility of CaMPARI in freely moving larvae of zebrafish and flies, and in head-fixed mice and adult flies.

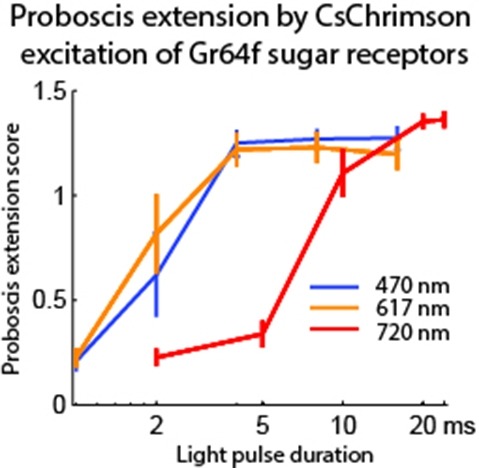

Optogenetic tools enable examination of how specific cell types contribute to brain circuit functions. A long-standing question is whether it is possible to independently activate two distinct neural populations in mammalian brain tissue. Such a capability would enable the study of how different synapses or pathways interact to encode information in the brain. Here we describe two channelrhodopsins, Chronos and Chrimson, discovered through sequencing and physiological characterization of opsins from over 100 species of alga. Chrimson’s excitation spectrum is red shifted by 45 nm relative to previous channelrhodopsins and can enable experiments in which red light is preferred. We show minimal visual system-mediated behavioral interference when using Chrimson in neurobehavioral studies in Drosophila melanogaster. Chronos has faster kinetics than previous channelrhodopsins yet is effectively more light sensitive. Together these two reagents enable two-color activation of neural spiking and downstream synaptic transmission in independent neural populations without detectable cross-talk in mouse brain slice.

Fluorescent protein-based sensors for detecting neuronal activity have been developed largely based on non-neuronal screening systems. However, the dynamics of neuronal state variables (e.g., voltage, calcium, etc.) are typically very rapid compared to those of non-excitable cells. We developed an electrical stimulation and fluorescence imaging platform based on dissociated rat primary neuronal cultures. We describe its use in testing genetically-encoded calcium indicators (GECIs). Efficient neuronal GECI expression was achieved using lentiviruses containing a neuronal-selective gene promoter. Action potentials (APs) and thus neuronal calcium levels were quantitatively controlled by electrical field stimulation, and fluorescence images were recorded. Images were segmented to extract fluorescence signals corresponding to individual GECI-expressing neurons, which improved sensitivity over full-field measurements. We demonstrate the superiority of screening GECIs in neurons compared with solution measurements. Neuronal screening was useful for efficient identification of variants with both improved response kinetics and high signal amplitudes. This platform can be used to screen many types of sensors with cellular resolution under realistic conditions where neuronal state variables are in relevant ranges with respect to timing and amplitude.

Many animals, including insects, are known to use visual landmarks to orient in their environment. In Drosophila melanogaster, behavioural genetics studies have identified a higher brain structure called the central complex as being required for the fly’s innate responses to vertical visual features and its short- and long-term memory for visual patterns. But whether and how neurons of the fly central complex represent visual features are unknown. Here we use two-photon calcium imaging in head-fixed walking and flying flies to probe visuomotor responses of ring neurons—a class of central complex neurons that have been implicated in landmark-driven spatial memory in walking flies and memory for visual patterns in tethered flying flies. We show that dendrites of ring neurons are visually responsive and arranged retinotopically. Ring neuron receptive fields comprise both excitatory and inhibitory subfields, resembling those of simple cells in the mammalian primary visual cortex. Ring neurons show strong and, in some cases, direction-selective orientation tuning, with a notable preference for vertically oriented features similar to those that evoke innate responses in flies. Visual responses were diminished during flight, but, in contrast with the hypothesized role of the central complex in the control of locomotion, not modulated during walking. Taken together, these results indicate that ring neurons represent behaviourally relevant visual features in the fly’s environment, enabling downstream central complex circuits to produce appropriate motor commands. More broadly, this study opens the door to mechanistic investigations of circuit computations underlying visually guided action selection in the Drosophila central complex.

Fluorescent calcium sensors are widely used to image neural activity. Using structure-based mutagenesis and neuron-based screening, we developed a family of ultrasensitive protein calcium sensors (GCaMP6) that outperformed other sensors in cultured neurons and in zebrafish, flies and mice in vivo. In layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons of the mouse visual cortex, GCaMP6 reliably detected single action potentials in neuronal somata and orientation-tuned synaptic calcium transients in individual dendritic spines. The orientation tuning of structurally persistent spines was largely stable over timescales of weeks. Orientation tuning averaged across spine populations predicted the tuning of their parent cell. Although the somata of GABAergic neurons showed little orientation tuning, their dendrites included highly tuned dendritic segments (5–40-µm long). GCaMP6 sensors thus provide new windows into the organization and dynamics of neural circuits over multiple spatial and temporal scales.

The visual neurons of many animals process sensory input differently depending on the animal’s state of locomotion. Now, new work in Drosophila melanogaster shows that neuromodulatory neurons active during flight boost responses of neurons in the visual system.

Genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs) are powerful tools for systems neuroscience. Recent efforts in protein engineering have significantly increased the performance of GECIs. The state-of-the art single-wavelength GECI, GCaMP3, has been deployed in a number of model organisms and can reliably detect three or more action potentials in short bursts in several systems in vivo . Through protein structure determination, targeted mutagenesis, high-throughput screening, and a battery of in vitro assays, we have increased the dynamic range of GCaMP3 by severalfold, creating a family of “GCaMP5” sensors. We tested GCaMP5s in several systems: cultured neurons and astrocytes, mouse retina, and in vivo in Caenorhabditis chemosensory neurons, Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction and adult antennal lobe, zebrafish retina and tectum, and mouse visual cortex. Signal-to-noise ratio was improved by at least 2- to 3-fold. In the visual cortex, two GCaMP5 variants detected twice as many visual stimulus-responsive cells as GCaMP3. By combining in vivo imaging with electrophysiology we show that GCaMP5 fluorescence provides a more reliable measure of neuronal activity than its predecessor GCaMP3.GCaMP5allows more sensitive detection of neural activity in vivo andmayfind widespread applications for cellular imaging in general.

Sensorimotor integration is a field rich in theory backed by a large body of psychophysical evidence. Relating the underlying neural circuitry to these theories has, however, been more challenging. With a wide array of complex behaviors coordinated by their small brains, insects provide powerful model systems to study key features of sensorimotor integration at a mechanistic level. Insect neural circuits perform both hard-wired and learned sensorimotor transformations. They modulate their neural processing based on both internal variables, such as the animal’s behavioral state, and external ones, such as the time of day. Here we present some studies using insect model systems that have produced insights, at the level of individual neurons, about sensorimotor integration and the various ways in which it can be modified by context.

The neural underpinnings of sensorimotor integration are best studied in the context of well-characterized behavior. A rich trove of Drosophila behavioral genetics research offers a variety of well-studied behaviors and candidate brain regions that can form the bases of such studies. The development of tools to perform in vivo physiology from the Drosophila brain has made it possible to monitor activity in defined neurons in response to sensory stimuli. More recently still, it has become possible to perform recordings from identified neurons in the brain of head-fixed flies during walking or flight behaviors. In this chapter, we discuss how experiments that simultaneously monitor behavior and physiology in Drosophila can be combined with other techniques to produce testable models of sensorimotor circuit function.

Changes in behavioral state modify neural activity in many systems. In some vertebrates such modulation has been observed and interpreted in the context of attention and sensorimotor coordinate transformations. Here we report state-dependent activity modulations during walking in a visual-motor pathway of Drosophila. We used two-photon imaging to monitor intracellular calcium activity in motion-sensitive lobula plate tangential cells (LPTCs) in head-fixed Drosophila walking on an air-supported ball. Cells of the horizontal system (HS)–a subgroup of LPTCs–showed stronger calcium transients in response to visual motion when flies were walking rather than resting. The amplified responses were also correlated with walking speed. Moreover, HS neurons showed a relatively higher gain in response strength at higher temporal frequencies, and their optimum temporal frequency was shifted toward higher motion speeds. Walking-dependent modulation of HS neurons in the Drosophila visual system may constitute a mechanism to facilitate processing of higher image speeds in behavioral contexts where these speeds of visual motion are relevant for course stabilization.