Filter

Associated Lab

- Druckmann Lab (3) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Fitzgerald Lab (1) Apply Fitzgerald Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (3) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (5) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Lee (Albert) Lab (1) Apply Lee (Albert) Lab filter

- Leonardo Lab (1) Apply Leonardo Lab filter

- Magee Lab (2) Apply Magee Lab filter

- Pachitariu Lab (1) Apply Pachitariu Lab filter

- Pastalkova Lab (1) Apply Pastalkova Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (4) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Romani Lab (43) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (1) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Spruston Lab (1) Apply Spruston Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (5) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

Associated Project Team

Publication Date

- 2024 (4) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (2) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (3) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (4) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (2) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (3) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (3) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (6) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (2) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (4) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (2) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (1) Apply 2013 filter

- 2011 (1) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (1) Apply 2010 filter

- 2008 (2) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (1) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (1) Apply 2006 filter

- 2005 (1) Apply 2005 filter

Type of Publication

43 Publications

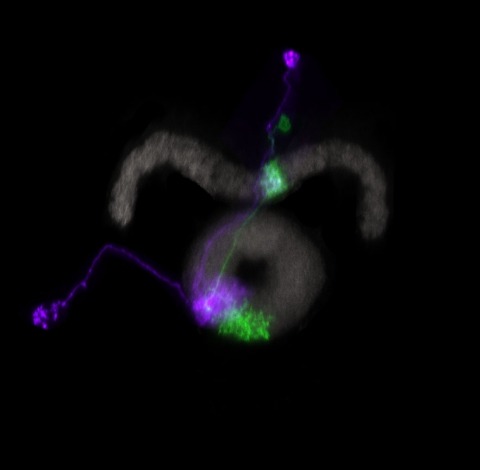

Showing 21-30 of 43 resultsA neuron that extracts directionally selective motion information from upstream signals lacking this selectivity must compare visual responses from spatially offset inputs. Distinguishing among prevailing algorithmic models for this computation requires measuring fast neuronal activity and inhibition. In the Drosophila melanogaster visual system, a fourth-order neuron-T4-is the first cell type in the ON pathway to exhibit directionally selective signals. Here we use in vivo whole-cell recordings of T4 to show that directional selectivity originates from simple integration of spatially offset fast excitatory and slow inhibitory inputs, resulting in a suppression of responses to the nonpreferred motion direction. We constructed a passive, conductance-based model of a T4 cell that accurately predicts the neuron's response to moving stimuli. These results connect the known circuit anatomy of the motion pathway to the algorithmic mechanism by which the direction of motion is computed.

Learning is primarily mediated by activity-dependent modifications of synaptic strength within neuronal circuits. We discovered that place fields in hippocampal area CA1 are produced by a synaptic potentiation notably different from Hebbian plasticity. Place fields could be produced in vivo in a single trial by potentiation of input that arrived seconds before and after complex spiking. The potentiated synaptic input was not initially coincident with action potentials or depolarization. This rule, named behavioral time scale synaptic plasticity, abruptly modifies inputs that were neither causal nor close in time to postsynaptic activation. In slices, five pairings of subthreshold presynaptic activity and calcium (Ca(2+)) plateau potentials produced a large potentiation with an asymmetric seconds-long time course. This plasticity efficiently stores entire behavioral sequences within synaptic weights to produce predictive place cell activity.

The dilemma that neurotheorists face is that (1) detailed biophysical models that can be constrained by direct measurements, while being of great importance, offer no immediate insights into cognitive processes in the brain, and (2) high-level abstract cognitive models, on the other hand, while relevant for understanding behavior, are largely detached from neuronal processes and typically have many free, experimentally unconstrained parameters that have to be tuned to a particular data set and, hence, cannot be readily generalized to other experimental paradigms. In this contribution, we propose a set of "first principles" for neurally inspired cognitive modeling of memory retrieval that has no biologically unconstrained parameters and can be analyzed mathematically both at neuronal and cognitive levels. We apply this framework to the classical cognitive paradigm of free recall. We show that the resulting model accounts well for puzzling behavioral data on human participants and makes predictions that could potentially be tested with neurophysiological recording techniques.

Hippocampal place cells represent different environments with distinct neural activity patterns. Following an abrupt switch between two familiar configurations of visual cues defining two environments, the hippocampal neural activity pattern switches almost immediately to the corresponding representation. Surprisingly, during a transient period following the switch to the new environment, occasional fast transitions of activity patterns between the representations (flickering) were observed (Jezek et al. 2011). Here we show that an attractor neural network model of place cells with connections endowed with short-term synaptic plasticity can account for this phenomenon. A memory trace of the recent history of network activity is maintained in the state of the synapses, allowing the network to temporarily reactivate the representation of the previous environment in the absence of the corresponding sensory cues. The model predicts that the number of flickering events depends on the amplitude of the ongoing theta rhythm and the distance between the current position of the animal and its position at the time of cue switching. We test these predictions with new analysis of experimental data. These results suggest a potential role of short-term synaptic plasticity in recruiting the activity of different cell assemblies and in shaping hippocampal activity of behaving animals. This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

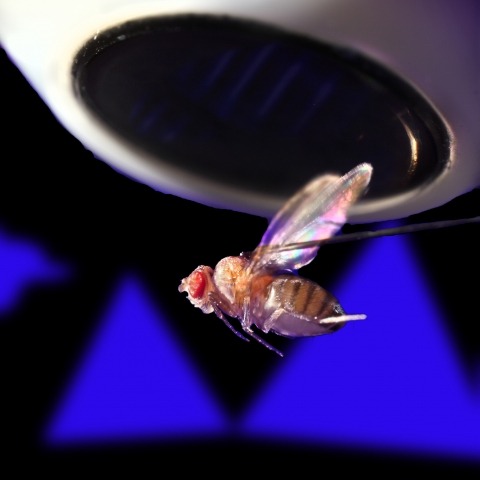

Many animals maintain an internal representation of their heading as they move through their surroundings. Such a compass representation was recently discovered in a neural population in the Drosophila melanogaster central complex, a brain region implicated in spatial navigation. Here, we use two-photon calcium imaging and electrophysiology in head-fixed walking flies to identify a different neural population that conjunctively encodes heading and angular velocity, and is excited selectively by turns in either the clockwise or counterclockwise direction. We show how these mirror-symmetric turn responses combine with the neurons' connectivity to the compass neurons to create an elegant mechanism for updating the fly's heading representation when the animal turns in darkness. This mechanism, which employs recurrent loops with an angular shift, bears a resemblance to those proposed in theoretical models for rodent head direction cells. Our results provide a striking example of structure matching function for a broadly relevant computation.

Ring attractors are a class of recurrent networks hypothesized to underlie the representation of heading direction. Such network structures, schematized as a ring of neurons whose connectivity depends on their heading preferences, can sustain a bump-like activity pattern whose location can be updated by continuous shifts along either turn direction. We recently reported that a population of fly neurons represents the animal's heading via bump-like activity dynamics. We combined two-photon calcium imaging in head-fixed flying flies with optogenetics to overwrite the existing population representation with an artificial one, which was then maintained by the circuit with naturalistic dynamics. A network with local excitation and global inhibition enforces this unique and persistent heading representation. Ring attractor networks have long been invoked in theoretical work; our study provides physiological evidence of their existence and functional architecture.

Place cells in the CA1 region of the hippocampus express location-specific firing despite receiving a steady barrage of heterogeneously tuned excitatory inputs that should compromise output dynamic range and timing. We examined the role of synaptic inhibition in countering the deleterious effects of off-target excitation. Intracellular recordings in behaving mice demonstrate that bimodal excitation drives place cells, while unimodal excitation drives weaker or no spatial tuning in interneurons. Optogenetic hyperpolarization of interneurons had spatially uniform effects on place cell membrane potential dynamics, substantially reducing spatial selectivity. These data and a computational model suggest that spatially uniform inhibitory conductance enhances rate coding in place cells by suppressing out-of-field excitation and by limiting dendritic amplification. Similarly, we observed that inhibitory suppression of phasic noise generated by out-of-field excitation enhances temporal coding by expanding the range of theta phase precession. Thus, spatially uniform inhibition allows proficient and flexible coding in hippocampal CA1 by suppressing heterogeneously tuned excitation.

Hippocampal place cells encode the animal's spatial position. However, it is unknown how different long-range sensory systems affect spatial representations. Here we alternated usage of vision and echolocation in Egyptian fruit bats while recording from single neurons in hippocampal areas CA1 and subiculum. Bats flew back and forth along a linear flight track, employing echolocation in darkness or vision in light. Hippocampal representations remapped between vision and echolocation via two kinds of remapping: subiculum neurons turned on or off, while CA1 neurons shifted their place fields. Interneurons also exhibited strong remapping. Finally, hippocampal place fields were sharper under vision than echolocation, matching the superior sensory resolution of vision over echolocation. Simulating several theoretical models of place-cells suggested that combining sensory information and path integration best explains the experimental sharpening data. In summary, here we show sensory-based global remapping in a mammal, suggesting that the hippocampus does not contain an abstract spatial map but rather a 'cognitive atlas', with multiple maps for different sensory modalities.

A large variability in performance is observed when participants recall briefly presented lists of words. The sources of such variability are not known. Our analysis of a large data set of free recall revealed a small fraction of participants that reached an extremely high performance, including many trials with the recall of complete lists. Moreover, some of them developed a number of consistent input-position-dependent recall strategies, in particular recalling words consecutively ("chaining") or in groups of consecutively presented words ("chunking"). The time course of acquisition and particular choice of positional grouping were variable among participants. Our results show that acquiring positional strategies plays a crucial role in improvement of recall performance.

Human memory can store large amount of information. Nevertheless, recalling is often a challenging task. In a classical free recall paradigm, where participants are asked to repeat a briefly presented list of words, people make mistakes for lists as short as 5 words. We present a model for memory retrieval based on a Hopfield neural network where transition between items are determined by similarities in their long-term memory representations. Meanfield analysis of the model reveals stable states of the network corresponding (1) to single memory representations and (2) intersection between memory representations. We show that oscillating feedback inhibition in the presence of noise induces transitions between these states triggering the retrieval of different memories. The network dynamics qualitatively predicts the distribution of time intervals required to recall new memory items observed in experiments. It shows that items having larger number of neurons in their representation are statistically easier to recall and reveals possible bottlenecks in our ability of retrieving memories. Overall, we propose a neural network model of information retrieval broadly compatible with experimental observations and is consistent with our recent graphical model (Romani et al., 2013).