Two types of neurons in the fly brain help a fly land when it detects a looming stimulus – but only if it’s already in flight.

For fruit flies, the shadow cast by a looming predator looks much the same as an approaching tree. But one triggers an escape response, while the other invites the fly to gently land.

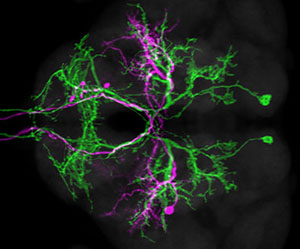

Flies can process the same visual cues differently depending on context, evoking the proper response based on the scenario, new research shows. Researchers at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus identified two pairs of neurons going from the brain to the ventral nerve cord that make a fly land in response to a looming shadow – but only if the insect is already in flight. When the fly is at rest, those circuits don’t respond to the looming stimulus, they report June 10, 2019, in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

“What was surprising is that there were two sets of landing neurons,” says study coauthor and Janelia Group Leader Gwyneth Card – and that they were driven by two different mechanisms. One type (a pair of matching neurons on each side of the brain) responded to a molecule called octopamine, a brain chemical that’s released when flies are in flight. The other type was activated independently of octopamine or other brain chemicals that the team tested, but still only responded to shadows when a fly was flapping its wings.

“What was surprising is that there were two sets of landing neurons,” says study coauthor and Janelia Group Leader Gwyneth Card – and that they were driven by two different mechanisms. One type (a pair of matching neurons on each side of the brain) responded to a molecule called octopamine, a brain chemical that’s released when flies are in flight. The other type was activated independently of octopamine or other brain chemicals that the team tested, but still only responded to shadows when a fly was flapping its wings.

Having two parallel gating mechanisms to enable landing behavior might be a way to make sure the pathway is only turned on when it’s supposed to be, says study lead author Jan Ache, a research scientist at Janelia.

It’s not yet clear what drives the flight dependence in the second set of landing neurons, though. Data from Janelia’s FlyEM Project Team, which is tracing the connections between all of the neurons in the fly brain, will help answer that question when it’s released soon.

###

Citation

Jan M. Ache, Shigehiro Namiki, Allen Lee, Kristin Branson, and Gwyneth M. Card. “State-dependent decoupling of sensory and motor circuits underlies behavioral flexibility in Drosophila.” Nature Neuroscience. Published online June 10, 2019. doi:10.1038/s41593-019-0413-4.

Media Contacts

Laurel Hamers

hamersl@janelia.hhmi.org