Filter

Result Type

- Apply filter

- Apply filter

- Apply filter

- Apply filter

- Apply filter

- Apply filter

- Apply filter

- Apply filter

- Apply filter

- Area Landing Page (8) Apply Area Landing Page filter

- Collaborations (2) Apply Collaborations filter

- Conferences (241) Apply Conferences filter

- Janelia Archives (19) Apply Janelia Archives filter

- Janelia Archives Landing (1) Apply Janelia Archives Landing filter

- Lab (59) Apply Lab filter

- News Stories (270) Apply News Stories filter

- Other (543) Apply Other filter

- People (646) Apply People filter

- Project Team (15) Apply Project Team filter

- Publications (2655) Apply Publications filter

- Support Team (21) Apply Support Team filter

- Theory Fellow Landing Page (4) Apply Theory Fellow Landing Page filter

- Tool (131) Apply Tool filter

Associated Lab

- Aguilera Castrejon Lab (6) Apply Aguilera Castrejon Lab filter

- Ahrens Lab (71) Apply Ahrens Lab filter

- Aso Lab (49) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Baker Lab (20) Apply Baker Lab filter

- Betzig Lab (111) Apply Betzig Lab filter

- Beyene Lab (14) Apply Beyene Lab filter

- Bock Lab (15) Apply Bock Lab filter

- Branson Lab (59) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Card Lab (36) Apply Card Lab filter

- Cardona Lab (44) Apply Cardona Lab filter

- Chklovskii Lab (10) Apply Chklovskii Lab filter

- Clapham Lab (23) Apply Clapham Lab filter

- Cui Lab (20) Apply Cui Lab filter

- Darshan Lab (8) Apply Darshan Lab filter

- Dennis Lab (7) Apply Dennis Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (34) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Druckmann Lab (21) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Dudman Lab (49) Apply Dudman Lab filter

- Eddy/Rivas Lab (30) Apply Eddy/Rivas Lab filter

- Egnor Lab (5) Apply Egnor Lab filter

- Espinosa Medina Lab (24) Apply Espinosa Medina Lab filter

- Feliciano Lab (14) Apply Feliciano Lab filter

- Fetter Lab (31) Apply Fetter Lab filter

- Fitzgerald Lab (16) Apply Fitzgerald Lab filter

- Freeman Lab (16) Apply Freeman Lab filter

- Funke Lab (45) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Gonen Lab (60) Apply Gonen Lab filter

- Grigorieff Lab (34) Apply Grigorieff Lab filter

- Harris Lab (62) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Heberlein Lab (15) Apply Heberlein Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (29) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Hess Lab (84) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Ilanges Lab (9) Apply Ilanges Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (57) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Ji Lab (34) Apply Ji Lab filter

- Johnson Lab (8) Apply Johnson Lab filter

- Kainmueller Lab (1) Apply Kainmueller Lab filter

- Karpova Lab (24) Apply Karpova Lab filter

- Keleman Lab (8) Apply Keleman Lab filter

- Keller Lab (80) Apply Keller Lab filter

- Koay Lab (8) Apply Koay Lab filter

- Lavis Lab (156) Apply Lavis Lab filter

- Lee (Albert) Lab (32) Apply Lee (Albert) Lab filter

- Leonardo Lab (19) Apply Leonardo Lab filter

- Li Lab (12) Apply Li Lab filter

- Lippincott-Schwartz Lab (108) Apply Lippincott-Schwartz Lab filter

- Liu (Yin) Lab (8) Apply Liu (Yin) Lab filter

- Liu (Zhe) Lab (65) Apply Liu (Zhe) Lab filter

- Looger Lab (143) Apply Looger Lab filter

- Magee Lab (31) Apply Magee Lab filter

- Menon Lab (12) Apply Menon Lab filter

- Murphy Lab (7) Apply Murphy Lab filter

- O'Shea Lab (12) Apply O'Shea Lab filter

- Otopalik Lab (9) Apply Otopalik Lab filter

- Pachitariu Lab (43) Apply Pachitariu Lab filter

- Pastalkova Lab (6) Apply Pastalkova Lab filter

- Pavlopoulos Lab (7) Apply Pavlopoulos Lab filter

- Pedram Lab (12) Apply Pedram Lab filter

- Podgorski Lab (19) Apply Podgorski Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (62) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Riddiford Lab (21) Apply Riddiford Lab filter

- Romani Lab (45) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (123) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Ryan Lab (1) Apply Ryan Lab filter

- Saalfeld Lab (58) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Satou Lab (8) Apply Satou Lab filter

- Scheffer Lab (39) Apply Scheffer Lab filter

- Schreiter Lab (64) Apply Schreiter Lab filter

- Sgro Lab (11) Apply Sgro Lab filter

- Shroff Lab (44) Apply Shroff Lab filter

- Simpson Lab (18) Apply Simpson Lab filter

- Singer Lab (39) Apply Singer Lab filter

- Spruston Lab (75) Apply Spruston Lab filter

- Stern Lab (84) Apply Stern Lab filter

- Sternson Lab (52) Apply Sternson Lab filter

- Stringer Lab (38) Apply Stringer Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (145) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

- Tebo Lab (20) Apply Tebo Lab filter

- Tervo Lab (14) Apply Tervo Lab filter

- Tillberg Lab (22) Apply Tillberg Lab filter

- Tjian Lab (19) Apply Tjian Lab filter

- Truman Lab (59) Apply Truman Lab filter

- Turaga Lab (53) Apply Turaga Lab filter

- Turner Lab (33) Apply Turner Lab filter

- Vale Lab (13) Apply Vale Lab filter

- Voigts Lab (9) Apply Voigts Lab filter

- Wang (Meng) Lab (30) Apply Wang (Meng) Lab filter

- Wang (Shaohe) Lab (11) Apply Wang (Shaohe) Lab filter

- Wong-Campos Lab (4) Apply Wong-Campos Lab filter

- Wu Lab (9) Apply Wu Lab filter

- Zlatic Lab (26) Apply Zlatic Lab filter

- Zuker Lab (5) Apply Zuker Lab filter

Associated Project Team

- CellMap (39) Apply CellMap filter

- COSEM (3) Apply COSEM filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (8) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fly Descending Interneuron (12) Apply Fly Descending Interneuron filter

- Fly Functional Connectome (15) Apply Fly Functional Connectome filter

- Fly Olympiad (5) Apply Fly Olympiad filter

- FlyEM (64) Apply FlyEM filter

- FlyLight (58) Apply FlyLight filter

- GENIE (67) Apply GENIE filter

- Integrative Imaging (3) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Larval Olympiad (2) Apply Larval Olympiad filter

- MouseLight (26) Apply MouseLight filter

- NeuroSeq (2) Apply NeuroSeq filter

- ThalamoSeq (1) Apply ThalamoSeq filter

- Tool Translation Team (T3) (36) Apply Tool Translation Team (T3) filter

- Transcription Imaging (48) Apply Transcription Imaging filter

Associated Support Team

- Project Pipeline Support (32) Apply Project Pipeline Support filter

- Anatomy and Histology (24) Apply Anatomy and Histology filter

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (43) Apply Cryo-Electron Microscopy filter

- Electron Microscopy (21) Apply Electron Microscopy filter

- Flow Cytometry (4) Apply Flow Cytometry filter

- Gene Targeting and Transgenics (19) Apply Gene Targeting and Transgenics filter

- Immortalized Cell Line Culture (6) Apply Immortalized Cell Line Culture filter

- Integrative Imaging (33) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Invertebrate Shared Resource (50) Apply Invertebrate Shared Resource filter

- Janelia Experimental Technology (103) Apply Janelia Experimental Technology filter

- Management Team (1) Apply Management Team filter

- Mass Spectrometry (4) Apply Mass Spectrometry filter

- Media Facil\ (6) Apply Media Facil\ filter

- Molecular Genomics (21) Apply Molecular Genomics filter

- Primary & iPS Cell Culture (24) Apply Primary & iPS Cell Culture filter

- Project Technical Resources (61) Apply Project Technical Resources filter

- Quantitative Genomics (26) Apply Quantitative Genomics filter

- Scientific Computing Software (129) Apply Scientific Computing Software filter

- Scientific Computing Systems (13) Apply Scientific Computing Systems filter

- Viral Tools (22) Apply Viral Tools filter

- Vivarium (10) Apply Vivarium filter

Publication Date

- 2025 (94) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (252) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (191) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (193) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (187) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (194) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (201) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (221) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (202) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (207) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (222) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (216) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (152) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (112) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (98) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (61) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (56) Apply 2009 filter

- 2008 (40) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (21) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (3) Apply 2006 filter

Tool Types

- Data (9) Apply Data filter

- Data Application (7) Apply Data Application filter

- Figshare (1) Apply Figshare filter

- Human Health (2) Apply Human Health filter

- Imaging Instrumentation (11) Apply Imaging Instrumentation filter

- Laboratory Hardware (3) Apply Laboratory Hardware filter

- Laboratory Tool (6) Apply Laboratory Tool filter

- Laboratory Tools (51) Apply Laboratory Tools filter

- Medical Technology (1) Apply Medical Technology filter

- Model Organisms (9) Apply Model Organisms filter

- Reagents (28) Apply Reagents filter

- Software (20) Apply Software filter

4771 Results

Showing 1301-1310 of 4771 resultsTo control reaching, the nervous system must generate large changes in muscle activation to drive the limb toward the target, and must also make smaller adjustments for precise and accurate behavior. Motor cortex controls the arm through projections to diverse targets across the central nervous system, but it has been challenging to identify the roles of cortical projections to specific targets. Here, we selectively disrupt cortico-cerebellar communication in the mouse by optogenetically stimulating the pontine nuclei in a cued reaching task. This perturbation did not typically block movement initiation, but degraded the precision, accuracy, duration, or success rate of the movement. Correspondingly, cerebellar and cortical activity during movement were largely preserved, but differences in hand velocity between control and stimulation conditions predicted from neural activity were correlated with observed velocity differences. These results suggest that while the total output of motor cortex drives reaching, the cortico-cerebellar loop makes small adjustments that contribute to the successful execution of this dexterous movement.

In their classic experiments, Olds and Milner showed that rats learn to lever press to receive an electric stimulus in specific brain regions. This led to the identification of mammalian reward centers. Our interest in defining the neuronal substrates of reward perception in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster prompted us to develop a simpler experimental approach wherein flies could implement behavior that induces self-stimulation of specific neurons in their brains. The high-throughput assay employs optogenetic activation of neurons when the fly occupies a specific area of a behavioral chamber, and the flies' preferential occupation of this area reflects their choosing to experience optogenetic stimulation. Flies in which neuropeptide F (NPF) neurons are activated display preference for the illuminated side of the chamber. We show that optogenetic activation of NPF neuron is rewarding in olfactory conditioning experiments and that the preference for NPF neuron activation is dependent on NPF signaling. Finally, we identify a small subset of NPF-expressing neurons located in the dorsomedial posterior brain that are sufficient to elicit preference in our assay. This assay provides the means for carrying out unbiased screens to map reward neurons in flies.

Sensory cues that precede reward acquire predictive (expected value) and incentive (drive reward-seeking action) properties. Mesolimbic dopamine neurons' responses to sensory cues correlate with both expected value and reward-seeking action. This has led to the proposal that phasic dopamine responses may be sufficient to inform value-based decisions, elicit actions, and/or induce motivational states; however, causal tests are incomplete. Here, we show that direct dopamine neuron stimulation, both calibrated to physiological and greater intensities, at the time of reward can be sufficient to induce and maintain reward seeking (reinforcing) although replacement of a cue with stimulation is insufficient to induce reward seeking or act as an informative cue. Stimulation of descending cortical inputs, one synapse upstream, are sufficient for reinforcement and cues to future reward. Thus, physiological activation of mesolimbic dopamine neurons can be sufficient for reinforcing properties of reward without being sufficient for the predictive and incentive properties of cues.

The mammalian hippocampus, comprised of serially connected subfields, participates in diverse behavioral and cognitive functions. It has been postulated that parallel circuitry embedded within hippocampal subfields may underlie such functional diversity. We sought to identify, delineate, and manipulate this putatively parallel architecture in the dorsal subiculum, the primary output subfield of the dorsal hippocampus. Population and single-cell RNA-seq revealed that the subiculum can be divided into two spatially adjacent subregions associated with prominent differences in pyramidal cell gene expression. Pyramidal cells occupying these two regions differed in their long-range inputs, local wiring, projection targets, and electrophysiological properties. Leveraging gene-expression differences across these regions, we use genetically restricted neuronal silencing to show that these regions differentially contribute to spatial working memory. This work provides a coherent molecular-, cellular-, circuit-, and behavioral-level demonstration that the hippocampus embeds structurally and functionally dissociable streams within its serial architecture.

Mouse visual cortex is subdivided into multiple distinct, hierarchically organized areas that are interconnected through feedforward (FF) and feedback (FB) pathways. The principal synaptic targets of FF and FB axons that reciprocally interconnect primary visual cortex (V1) with the higher lateromedial extrastriate area (LM) are pyramidal cells (Pyr) and parvalbumin (PV)-expressing GABAergic interneurons. Recordings in slices of mouse visual cortex have shown that layer 2/3 Pyr cells receive excitatory monosynaptic FF and FB inputs, which are opposed by disynaptic inhibition. Most notably, inhibition is stronger in the FF than FB pathway, suggesting pathway-specific organization of feedforward inhibition (FFI). To explore the hypothesis that this difference is due to diverse pathway-specific strengths of the inputs to PV neurons we have performed subcellular Channelrhodopsin-2-assisted circuit mapping in slices of mouse visual cortex. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were obtained from retrobead-labeled FFV1→LM- and FBLM→V1-projecting Pyr cells, as well as from tdTomato-expressing PV neurons. The results show that the FFV1→LM pathway provides on average 3.7-fold stronger depolarizing input to layer 2/3 inhibitory PV neurons than to neighboring excitatory Pyr cells. In the FBLM→V1 pathway, depolarizing inputs to layer 2/3 PV neurons and Pyr cells were balanced. Balanced inputs were also found in the FFV1→LM pathway to layer 5 PV neurons and Pyr cells, whereas FBLM→V1 inputs to layer 5 were biased toward Pyr cells. The findings indicate that FFI in FFV1→LM and FBLM→V1 circuits are organized in a pathway- and lamina-specific fashion.

The superficial layers of the superior colliculus (sSC) receive retinal input and project to thalamic regions - the dorsal lateral geniculate (dLGN) and lateral posterior (LP; or pulvinar) nuclei -that convey visual information to cortex. A critical step towards understanding the functional impact of sSC neurons on these parallel thalamo-cortical pathways is determining whether different classes of sSC neurons, which are known to respond to different features of visual stimuli, innervate overlapping or distinct thalamic targets. Here, we identified a transgenic mouse line that labels sSC neurons that project to dLGN but not LP. We utilized selective expression of fluorophores and channelrhodopsin in this and previously characterized mouse lines to demonstrate that distinct cell types give rise to sSC projections to dLGN and LP. We further show that the glutamatergic sSC cell type that projects to dLGN also provides input to the sSC cell type that projects to LP. These results clarify the cellular origin of parallel sSC-thalamo-cortical pathways and reveal an interaction between these pathways via local connections within the sSC.

Activity in the motor cortex predicts movements, seconds before they are initiated. This preparatory activity has been observed across cortical layers, including in descending pyramidal tract neurons in layer 5. A key question is how preparatory activity is maintained without causing movement, and is ultimately converted to a motor command to trigger appropriate movements. Here, using single-cell transcriptional profiling and axonal reconstructions, we identify two types of pyramidal tract neuron. Both types project to several targets in the basal ganglia and brainstem. One type projects to thalamic regions that connect back to motor cortex; populations of these neurons produced early preparatory activity that persisted until the movement was initiated. The second type projects to motor centres in the medulla and mainly produced late preparatory activity and motor commands. These results indicate that two types of motor cortex output neurons have specialized roles in motor control.

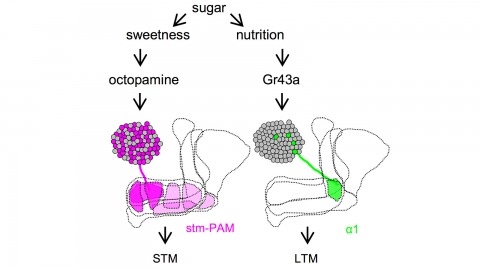

Drosophila melanogaster can acquire a stable appetitive olfactory memory when the presentation of a sugar reward and an odor are paired. However, the neuronal mechanisms by which a single training induces long-term memory are poorly understood. Here we show that two distinct subsets of dopamine neurons in the fly brain signal reward for short-term (STM) and long-term memories (LTM). One subset induces memory that decays within several hours, whereas the other induces memory that gradually develops after training. They convey reward signals to spatially segregated synaptic domains of the mushroom body (MB), a potential site for convergence. Furthermore, we identified a single type of dopamine neuron that conveys the reward signal to restricted subdomains of the mushroom body lobes and induces long-term memory. Constant appetitive memory retention after a single training session thus comprises two memory components triggered by distinct dopamine neurons.

Pigmentation divergence between Drosophila species has emerged as a model trait for studying the genetic basis of phenotypic evolution, with genetic changes contributing to pigmentation differences often mapping to genes in the pigment synthesis pathway and their regulators. These studies of Drosophila pigmentation have tended to focus on pigmentation changes in one body part for a particular pair of species, but changes in pigmentation are often observed in multiple body parts between the same pair of species. The similarities and differences of genetic changes responsible for divergent pigmentation in different body parts of the same species thus remain largely unknown. Here we compare the genetic basis of pigmentation divergence between Drosophila elegans and D. gunungcola in the wing, legs, and thorax. Prior work has shown that regions of the genome containing the pigmentation genes yellow and ebony influence the size of divergent male-specific wing spots between these two species. We find that these same two regions of the genome underlie differences in leg and thorax pigmentation; however, divergent alleles in these regions show differences in allelic dominance and epistasis among the three body parts. These complex patterns of inheritance can be explained by a model of evolution involving tissue-specific changes in the expression of Yellow and Ebony between D. elegans and D. gunungcola.