Filter

Associated Lab

- Aso Lab (30) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Betzig Lab (1) Apply Betzig Lab filter

- Bock Lab (2) Apply Bock Lab filter

- Branson Lab (8) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Card Lab (5) Apply Card Lab filter

- Clapham Lab (1) Apply Clapham Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (2) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Druckmann Lab (1) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Fetter Lab (1) Apply Fetter Lab filter

- Funke Lab (1) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Harris Lab (3) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Heberlein Lab (1) Apply Heberlein Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (2) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Hess Lab (5) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (6) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Lippincott-Schwartz Lab (1) Apply Lippincott-Schwartz Lab filter

- Looger Lab (2) Apply Looger Lab filter

- O'Shea Lab (1) Apply O'Shea Lab filter

- Otopalik Lab (1) Apply Otopalik Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (15) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Riddiford Lab (1) Apply Riddiford Lab filter

- Romani Lab (1) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Remove Rubin Lab filter Rubin Lab

- Saalfeld Lab (4) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Scheffer Lab (7) Apply Scheffer Lab filter

- Schreiter Lab (1) Apply Schreiter Lab filter

- Simpson Lab (3) Apply Simpson Lab filter

- Singer Lab (1) Apply Singer Lab filter

- Spruston Lab (1) Apply Spruston Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (3) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

- Truman Lab (4) Apply Truman Lab filter

- Turaga Lab (1) Apply Turaga Lab filter

- Turner Lab (5) Apply Turner Lab filter

Associated Project Team

- CellMap (1) Apply CellMap filter

- Fly Functional Connectome (4) Apply Fly Functional Connectome filter

- Fly Olympiad (3) Apply Fly Olympiad filter

- FlyEM (11) Apply FlyEM filter

- FlyLight (20) Apply FlyLight filter

- GENIE (1) Apply GENIE filter

- Transcription Imaging (1) Apply Transcription Imaging filter

Associated Support Team

- Project Pipeline Support (1) Apply Project Pipeline Support filter

- Electron Microscopy (4) Apply Electron Microscopy filter

- Invertebrate Shared Resource (9) Apply Invertebrate Shared Resource filter

- Janelia Experimental Technology (1) Apply Janelia Experimental Technology filter

- Management Team (1) Apply Management Team filter

- Primary & iPS Cell Culture (1) Apply Primary & iPS Cell Culture filter

- Project Technical Resources (11) Apply Project Technical Resources filter

- Quantitative Genomics (2) Apply Quantitative Genomics filter

- Scientific Computing Software (12) Apply Scientific Computing Software filter

- Scientific Computing Systems (2) Apply Scientific Computing Systems filter

Publication Date

- 2025 (4) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (4) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (5) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (1) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (4) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (9) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (6) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (7) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (15) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (3) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (16) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (8) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (5) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (7) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (3) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (2) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (1) Apply 2009 filter

- 2008 (2) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (2) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (1) Apply 2006 filter

105 Janelia Publications

Showing 21-30 of 105 resultsThe fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster is an important model organism for neuroscience with a wide array of genetic tools that enable the mapping of individuals neurons and neural subtypes. Brain templates are essential for comparative biological studies because they enable analyzing many individuals in a common reference space. Several central brain templates exist for Drosophila, but every one is either biased, uses sub-optimal tissue preparation, is imaged at low resolution, or does not account for artifacts. No publicly available Drosophila ventral nerve cord template currently exists. In this work, we created high-resolution templates of the Drosophila brain and ventral nerve cord using the best-available technologies for imaging, artifact correction, stitching, and template construction using groupwise registration. We evaluated our central brain template against the four most competitive, publicly available brain templates and demonstrate that ours enables more accurate registration with fewer local deformations in shorter time.

Many animals maintain an internal representation of their heading as they move through their surroundings. Such a compass representation was recently discovered in a neural population in the Drosophila melanogaster central complex, a brain region implicated in spatial navigation. Here, we use two-photon calcium imaging and electrophysiology in head-fixed walking flies to identify a different neural population that conjunctively encodes heading and angular velocity, and is excited selectively by turns in either the clockwise or counterclockwise direction. We show how these mirror-symmetric turn responses combine with the neurons' connectivity to the compass neurons to create an elegant mechanism for updating the fly's heading representation when the animal turns in darkness. This mechanism, which employs recurrent loops with an angular shift, bears a resemblance to those proposed in theoretical models for rodent head direction cells. Our results provide a striking example of structure matching function for a broadly relevant computation.

The behavioral state of an animal can dynamically modulate visual processing. In flies, the behavioral state is known to alter the temporal tuning of neurons that carry visual motion information into the central brain. However, where this modulation occurs and how it tunes the properties of this neural circuit are not well understood. Here, we show that the behavioral state alters the baseline activity levels and the temporal tuning of the first directionally selective neuron in the ON motion pathway (T4) as well as its primary input neurons (Mi1, Tm3, Mi4, Mi9). These effects are especially prominent in the inhibitory neuron Mi4, and we show that central octopaminergic neurons provide input to Mi4 and increase its excitability. We further show that octopamine neurons are required for sustained behavioral responses to fast-moving, but not slow-moving, visual stimuli in walking flies. These results indicate that behavioral-state modulation acts directly on the inputs to the directionally selective neurons and supports efficient neural coding of motion stimuli.

Analyzing Drosophila melanogaster neural expression patterns in thousands of three-dimensional image stacks of individual brains requires registering them into a canonical framework based on a fiducial reference of neuropil morphology. Given a target brain labeled with predefined landmarks, the BrainAligner program automatically finds the corresponding landmarks in a subject brain and maps it to the coordinate system of the target brain via a deformable warp. Using a neuropil marker (the antibody nc82) as a reference of the brain morphology and a target brain that is itself a statistical average of data for 295 brains, we achieved a registration accuracy of 2 μm on average, permitting assessment of stereotypy, potential connectivity and functional mapping of the adult fruit fly brain. We used BrainAligner to generate an image pattern atlas of 2954 registered brains containing 470 different expression patterns that cover all the major compartments of the fly brain.

Persistent internal states are important for maintaining survival-promoting behaviors, such as aggression. In female Drosophila melanogaster, we have previously shown that individually activating either aIPg or pC1d cell types can induce aggression. Here we investigate further the individual roles of these cholinergic, sexually dimorphic cell types, and the reciprocal connections between them, in generating a persistent aggressive internal state. We find that a brief 30-second optogenetic stimulation of aIPg neurons was sufficient to promote an aggressive internal state lasting at least 10 minutes, whereas similar stimulation of pC1d neurons did not. While we previously showed that stimulation of pC1e alone does not evoke aggression, persistent behavior could be promoted through simultaneous stimulation of pC1d and pC1e, suggesting an unexpected synergy of these cell types in establishing a persistent aggressive state. Neither aIPg nor pC1d show persistent neuronal activity themselves, implying that the persistent internal state is maintained by other mechanisms. Moreover, inactivation of pC1d did not significantly reduce aIPg-evoked persistent aggression arguing that the aggressive state did not depend on pC1d-aIPg recurrent connectivity. Our results suggest the need for alternative models to explain persistent female aggression.

The central complex (CX) plays a key role in many higher-order functions of the insect brain including navigation and activity regulation. Genetic tools for manipulating individual cell types, and knowledge of what neurotransmitters and neuromodulators they express, will be required to gain mechanistic understanding of how these functions are implemented. We generated and characterized split-GAL4 driver lines that express in individual or small subsets of about half of CX cell types. We surveyed neuropeptide and neuropeptide receptor expression in the central brain using fluorescent in situ hybridization. About half of the neuropeptides we examined were expressed in only a few cells, while the rest were expressed in dozens to hundreds of cells. Neuropeptide receptors were expressed more broadly and at lower levels. Using our GAL4 drivers to mark individual cell types, we found that 51 of the 85 CX cell types we examined expressed at least one neuropeptide and 21 expressed multiple neuropeptides. Surprisingly, all co-expressed a small neurotransmitter. Finally, we used our driver lines to identify CX cell types whose activation affects sleep, and identified other central brain cell types that link the circadian clock to the CX. The well-characterized genetic tools and information on neuropeptide and neurotransmitter expression we provide should enhance studies of the CX.

The central complex (CX) plays a key role in many higher-order functions of the insect brain including navigation and activity regulation. Genetic tools for manipulating individual cell types, and knowledge of what neurotransmitters and neuromodulators they express, will be required to gain mechanistic understanding of how these functions are implemented. We generated and characterized split-GAL4 driver lines that express in individual or small subsets of about half of CX cell types. We surveyed neuropeptide and neuropeptide receptor expression in the central brain using fluorescent in situ hybridization. About half of the neuropeptides we examined were expressed in only a few cells, while the rest were expressed in dozens to hundreds of cells. Neuropeptide receptors were expressed more broadly and at lower levels. Using our GAL4 drivers to mark individual cell types, we found that 51 of the 85 CX cell types we examined expressed at least one neuropeptide and 21 expressed multiple neuropeptides. Surprisingly, all co-expressed a small neurotransmitter. Finally, we used our driver lines to identify CX cell types whose activation affects sleep, and identified other central brain cell types that link the circadian clock to the CX. The well-characterized genetic tools and information on neuropeptide and neurotransmitter expression we provide should enhance studies of the CX.

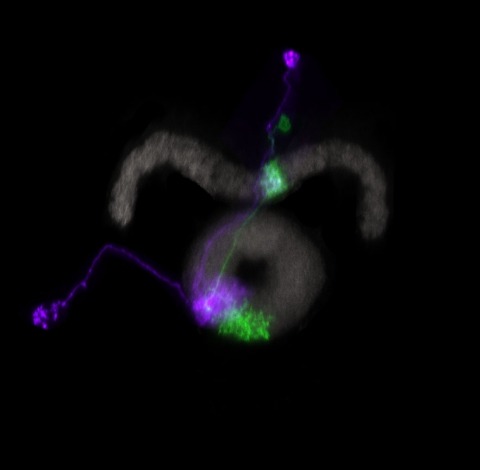

Aggressive social interactions are used to compete for limited resources and are regulated by complex sensory cues and the organism's internal state. While both sexes exhibit aggression, its neuronal underpinnings are understudied in females. Here, we identify a population of sexually dimorphic aIPg neurons in the adult central brain whose optogenetic activation increased, and genetic inactivation reduced, female aggression. Analysis of GAL4 lines identified in an unbiased screen for increased female chasing behavior revealed the involvement of another sexually dimorphic neuron, pC1d, and implicated aIPg and pC1d neurons as core nodes regulating female aggression. Connectomic analysis demonstrated that aIPg neurons and pC1d are interconnected and suggest that aIPg neurons may exert part of their effect by gating the flow of visual information to descending neurons. Our work reveals important regulatory components of the neuronal circuitry that underlies female aggressive social interactions and provides tools for their manipulation.

The study of synaptic specificity and plasticity in the CNS is limited by the inability to efficiently visualize synapses in identified neurons using light microscopy. Here, we describe synaptic tagging with recombination (STaR), a method for labeling endogenous presynaptic and postsynaptic proteins in a cell-type-specific fashion. We modified genomic loci encoding synaptic proteins within bacterial artificial chromosomes such that these proteins, expressed at endogenous levels and with normal spatiotemporal patterns, were labeled in an inducible fashion in specific neurons through targeted expression of site-specific recombinases. Within the Drosophila visual system, the number and distribution of synapses correlate with electron microscopy studies. Using two different recombination systems, presynaptic and postsynaptic specializations of synaptic pairs can be colabeled. STaR also allows synapses within the CNS to be studied in live animals noninvasively. In principle, STaR can be adapted to the mammalian nervous system.