Filter

Associated Lab

- Aso Lab (9) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Branson Lab (2) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Card Lab (4) Apply Card Lab filter

- Cardona Lab (2) Apply Cardona Lab filter

- Darshan Lab (1) Apply Darshan Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (4) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Espinosa Medina Lab (2) Apply Espinosa Medina Lab filter

- Fitzgerald Lab (1) Apply Fitzgerald Lab filter

- Funke Lab (1) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Heberlein Lab (1) Apply Heberlein Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (2) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (3) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Looger Lab (1) Apply Looger Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (6) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Romani Lab (2) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (9) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Stern Lab (3) Apply Stern Lab filter

- Truman Lab (2) Apply Truman Lab filter

- Turner Lab (4) Apply Turner Lab filter

- Zlatic Lab (1) Apply Zlatic Lab filter

Associated Project Team

Associated Support Team

- Project Pipeline Support (1) Apply Project Pipeline Support filter

- Electron Microscopy (1) Apply Electron Microscopy filter

- Remove Invertebrate Shared Resource filter Invertebrate Shared Resource

- Janelia Experimental Technology (6) Apply Janelia Experimental Technology filter

- Molecular Genomics (3) Apply Molecular Genomics filter

- Project Technical Resources (14) Apply Project Technical Resources filter

- Quantitative Genomics (4) Apply Quantitative Genomics filter

- Scientific Computing Software (4) Apply Scientific Computing Software filter

Publication Date

40 Janelia Publications

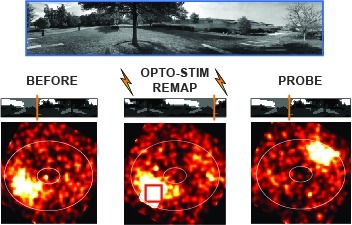

Showing 21-30 of 40 resultsMany animals rely on an internal heading representation when navigating in varied environments. How this representation is linked to the sensory cues that define different surroundings is unclear. In the fly brain, heading is represented by 'compass' neurons that innervate a ring-shaped structure known as the ellipsoid body. Each compass neuron receives inputs from 'ring' neurons that are selective for particular visual features; this combination provides an ideal substrate for the extraction of directional information from a visual scene. Here we combine two-photon calcium imaging and optogenetics in tethered flying flies with circuit modelling, and show how the correlated activity of compass and visual neurons drives plasticity, which flexibly transforms two-dimensional visual cues into a stable heading representation. We also describe how this plasticity enables the fly to convert a partial heading representation, established from orienting within part of a novel setting, into a complete heading representation. Our results provide mechanistic insight into the memory-related computations that are essential for flexible navigation in varied surroundings.

The ability to reproducibly target expression of transgenes to small, defined subsets of cells is a key experimental tool for understanding many biological processes. The Drosophila nervous system contains thousands of distinct cell types and it has generally not been possible to limit expression to one or a few cell types when using a single segment of genomic DNA as an enhancer to drive expression. Intersectional methods, in which expression of the transgene only occurs where two different enhancers overlap in their expression patterns, can be used to achieve the desired specificity. This report describes a set of over 2,800 transgenic lines for use with the split-GAL4 intersectional method.

Dopaminergic neurons with distinct projection patterns and physiological properties compose memory subsystems in a brain. However, it is poorly understood whether or how they interact during complex learning. Here, we identify a feedforward circuit formed between dopamine subsystems and show that it is essential for second-order conditioning, an ethologically important form of higher-order associative learning. The Drosophila mushroom body comprises a series of dopaminergic compartments, each of which exhibits distinct memory dynamics. We find that a slow and stable memory compartment can serve as an effective “teacher” by instructing other faster and transient memory compartments via a single key interneuron, which we identify by connectome analysis and neurotransmitter prediction. This excitatory interneuron acquires enhanced response to reward-predicting odor after first-order conditioning and, upon activation, evokes dopamine release in the “student” compartments. These hierarchical connections between dopamine subsystems explain distinct properties of first- and second-order memory long known by behavioral psychologists.

Nervous systems have the ability to select appropriate actions and action sequences in response to sensory cues. The circuit mechanisms by which nervous systems achieve choice, stability and transitions between behaviors are still incompletely understood. To identify neurons and brain areas involved in controlling these processes, we combined a large-scale neuronal inactivation screen with automated action detection in response to a mechanosensory cue in Drosophila larva. We analyzed behaviors from 2.9x105 larvae and identified 66 candidate lines for mechanosensory responses out of which 25 for competitive interactions between actions. We further characterize in detail the neurons in these lines and analyzed their connectivity using electron microscopy. We found the neurons in the mechanosensory network are located in different regions of the nervous system consistent with a distributed model of sensorimotor decision-making. These findings provide the basis for understanding how selection and transition between behaviors are controlled by the nervous system.

How memories are used by the brain to guide future action is poorly understood. In olfactory associative learning in Drosophila, multiple compartments of the mushroom body act in parallel to assign valence to a stimulus. Here, we show that appetitive memories stored in different compartments induce different levels of upwind locomotion. Using a photoactivation screen of a new collection of split-GAL4 drivers and EM connectomics, we identified a cluster of neurons postsynaptic to the mushroom body output neurons (MBONs) that can trigger robust upwind steering. These UpWind Neurons (UpWiNs) integrate inhibitory and excitatory synaptic inputs from MBONs of appetitive and aversive memory compartments, respectively. After training, disinhibition from the appetitive-memory MBONs enhances the response of UpWiNs to reward-predicting odors. Blocking UpWiNs impaired appetitive memory and reduced upwind locomotion during retrieval. Photoactivation of UpWiNs also increased the chance of returning to a location where activation was initiated, suggesting an additional role in olfactory navigation. Thus, our results provide insight into how learned abstract valences are gradually transformed into concrete memory-driven actions through divergent and convergent networks, a neuronal architecture that is commonly found in the vertebrate and invertebrate brains.

Choosing a mate is one of the most consequential decisions a female will make during her lifetime. A female fly signals her willingness to mate by opening her vaginal plates, allowing a courting male to copulate. Vaginal plate opening (VPO) occurs in response to the male courtship song and is dependent on the mating status of the female. How these exteroceptive (song) and interoceptive (mating status) inputs are integrated to regulate VPO remains unknown. Here we characterize the neural circuitry that implements mating decisions in the brain of female Drosophila melanogaster. We show that VPO is controlled by a pair of female-specific descending neurons (vpoDNs). The vpoDNs receive excitatory input from auditory neurons (vpoENs), which are tuned to specific features of the D. melanogaster song, and from pC1 neurons, which encode the mating status of the female. The song responses of vpoDNs, but not vpoENs, are attenuated upon mating, accounting for the reduced receptivity of mated females. This modulation is mediated by pC1 neurons. The vpoDNs thus directly integrate the external and internal signals that control the mating decisions of Drosophila females.

Mating and egg laying are tightly cooordinated events in the reproductive life of all oviparous females. Oviposition is typically rare in virgin females but is initiated after copulation. Here we identify the neural circuitry that links egg laying to mating status in Drosophila melanogaster. Activation of female-specific oviposition descending neurons (oviDNs) is necessary and sufficient for egg laying, and is equally potent in virgin and mated females. After mating, sex peptide-a protein from the male seminal fluid-triggers many behavioural and physiological changes in the female, including the onset of egg laying. Sex peptide is detected by sensory neurons in the uterus, and silences these neurons and their postsynaptic ascending neurons in the abdominal ganglion. We show that these abdominal ganglion neurons directly activate the female-specific pC1 neurons. GABAergic (γ-aminobutyric-acid-releasing) oviposition inhibitory neurons (oviINs) mediate feed-forward inhibition from pC1 neurons to both oviDNs and their major excitatory input, the oviposition excitatory neurons (oviENs). By attenuating the abdominal ganglion inputs to pC1 neurons and oviINs, sex peptide disinhibits oviDNs to enable egg laying after mating. This circuitry thus coordinates the two key events in female reproduction: mating and egg laying.

How memories of past events influence behavior is a key question in neuroscience. The major associative learning center in Drosophila, the Mushroom Body (MB), communicates to the rest of the brain through Mushroom Body Output Neurons (MBONs). While 21 MBON cell types have their dendrites confined to small compartments of the MB lobes, analysis of EM connectomes revealed the presence of an additional 14 MBON cell types that are atypical in having dendritic input both within the MB lobes and in adjacent brain regions. Genetic reagents for manipulating atypical MBONs and experimental data on their functions has been lacking. In this report we describe new cell-type-specific GAL4 drivers for many MBONs, including the majority of atypical MBONs. Using these genetic reagents, we conducted optogenetic activation screening to examine their ability to drive behaviors and learning. These reagents provide important new tools for the study of complex behaviors in Drosophila.

Animals employ diverse learning rules and synaptic plasticity dynamics to record temporal and statistical information about the world. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying this diversity are poorly understood. The anatomically defined compartments of the insect mushroom body function as parallel units of associative learning, with different learning rates, memory decay dynamics and flexibility (Aso & Rubin 2016). Here we show that nitric oxide (NO) acts as a neurotransmitter in a subset of dopaminergic neurons in . NO's effects develop more slowly than those of dopamine and depend on soluble guanylate cyclase in postsynaptic Kenyon cells. NO acts antagonistically to dopamine; it shortens memory retention and facilitates the rapid updating of memories. The interplay of NO and dopamine enables memories stored in local domains along Kenyon cell axons to be specialized for predicting the value of odors based only on recent events. Our results provide key mechanistic insights into how diverse memory dynamics are established in parallel memory systems.

Memory guides the choices an animal makes across widely varying conditions in dynamic environments. Consequently, the most adaptive choice depends on the options available. How can a single memory support optimal behavior across different sets of choice options? We address this using olfactory learning in Drosophila. Even when we restrict an odor-punishment association to a single set of synapses using optogenetics, we find that flies still show choice behavior that depends on the options it encounters. Here we show that how the odor choices are presented to the animal influences memory recall itself. Presenting two similar odors in sequence enabled flies to not only discriminate them behaviorally but also at the level of neural activity. However, when the same odors were encountered as solitary stimuli, no such differences were detectable. These results show that memory recall is not simply a comparison to a static learned template, but can be adaptively modulated by stimulus dynamics.