Filter

Associated Lab

- Aguilera Castrejon Lab (1) Apply Aguilera Castrejon Lab filter

- Ahrens Lab (53) Apply Ahrens Lab filter

- Aso Lab (40) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Baker Lab (19) Apply Baker Lab filter

- Betzig Lab (101) Apply Betzig Lab filter

- Beyene Lab (8) Apply Beyene Lab filter

- Bock Lab (14) Apply Bock Lab filter

- Branson Lab (50) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Card Lab (36) Apply Card Lab filter

- Cardona Lab (45) Apply Cardona Lab filter

- Chklovskii Lab (10) Apply Chklovskii Lab filter

- Clapham Lab (14) Apply Clapham Lab filter

- Cui Lab (19) Apply Cui Lab filter

- Darshan Lab (8) Apply Darshan Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (32) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Druckmann Lab (21) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Dudman Lab (38) Apply Dudman Lab filter

- Eddy/Rivas Lab (30) Apply Eddy/Rivas Lab filter

- Egnor Lab (4) Apply Egnor Lab filter

- Espinosa Medina Lab (15) Apply Espinosa Medina Lab filter

- Feliciano Lab (7) Apply Feliciano Lab filter

- Fetter Lab (31) Apply Fetter Lab filter

- Fitzgerald Lab (16) Apply Fitzgerald Lab filter

- Freeman Lab (15) Apply Freeman Lab filter

- Funke Lab (38) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Gonen Lab (59) Apply Gonen Lab filter

- Grigorieff Lab (34) Apply Grigorieff Lab filter

- Harris Lab (53) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Heberlein Lab (13) Apply Heberlein Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (23) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Hess Lab (74) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Ilanges Lab (2) Apply Ilanges Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (42) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Ji Lab (33) Apply Ji Lab filter

- Johnson Lab (1) Apply Johnson Lab filter

- Karpova Lab (13) Apply Karpova Lab filter

- Keleman Lab (8) Apply Keleman Lab filter

- Keller Lab (61) Apply Keller Lab filter

- Koay Lab (2) Apply Koay Lab filter

- Lavis Lab (137) Apply Lavis Lab filter

- Lee (Albert) Lab (29) Apply Lee (Albert) Lab filter

- Leonardo Lab (19) Apply Leonardo Lab filter

- Li Lab (4) Apply Li Lab filter

- Lippincott-Schwartz Lab (97) Apply Lippincott-Schwartz Lab filter

- Liu (Yin) Lab (1) Apply Liu (Yin) Lab filter

- Liu (Zhe) Lab (58) Apply Liu (Zhe) Lab filter

- Looger Lab (137) Apply Looger Lab filter

- Magee Lab (31) Apply Magee Lab filter

- Menon Lab (12) Apply Menon Lab filter

- Murphy Lab (6) Apply Murphy Lab filter

- O'Shea Lab (6) Apply O'Shea Lab filter

- Otopalik Lab (1) Apply Otopalik Lab filter

- Pachitariu Lab (36) Apply Pachitariu Lab filter

- Pastalkova Lab (5) Apply Pastalkova Lab filter

- Pavlopoulos Lab (7) Apply Pavlopoulos Lab filter

- Pedram Lab (4) Apply Pedram Lab filter

- Podgorski Lab (16) Apply Podgorski Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (45) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Riddiford Lab (20) Apply Riddiford Lab filter

- Romani Lab (31) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (105) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Saalfeld Lab (46) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Satou Lab (1) Apply Satou Lab filter

- Scheffer Lab (36) Apply Scheffer Lab filter

- Schreiter Lab (50) Apply Schreiter Lab filter

- Sgro Lab (1) Apply Sgro Lab filter

- Shroff Lab (31) Apply Shroff Lab filter

- Simpson Lab (18) Apply Simpson Lab filter

- Singer Lab (37) Apply Singer Lab filter

- Spruston Lab (57) Apply Spruston Lab filter

- Stern Lab (73) Apply Stern Lab filter

- Sternson Lab (47) Apply Sternson Lab filter

- Stringer Lab (32) Apply Stringer Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (131) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

- Tebo Lab (9) Apply Tebo Lab filter

- Tervo Lab (9) Apply Tervo Lab filter

- Tillberg Lab (18) Apply Tillberg Lab filter

- Tjian Lab (17) Apply Tjian Lab filter

- Truman Lab (58) Apply Truman Lab filter

- Turaga Lab (39) Apply Turaga Lab filter

- Turner Lab (27) Apply Turner Lab filter

- Vale Lab (7) Apply Vale Lab filter

- Voigts Lab (3) Apply Voigts Lab filter

- Wang (Meng) Lab (21) Apply Wang (Meng) Lab filter

- Wang (Shaohe) Lab (6) Apply Wang (Shaohe) Lab filter

- Wu Lab (8) Apply Wu Lab filter

- Zlatic Lab (26) Apply Zlatic Lab filter

- Zuker Lab (5) Apply Zuker Lab filter

Associated Project Team

- CellMap (12) Apply CellMap filter

- COSEM (3) Apply COSEM filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (3) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fly Descending Interneuron (11) Apply Fly Descending Interneuron filter

- Fly Functional Connectome (14) Apply Fly Functional Connectome filter

- Fly Olympiad (5) Apply Fly Olympiad filter

- FlyEM (53) Apply FlyEM filter

- FlyLight (49) Apply FlyLight filter

- GENIE (46) Apply GENIE filter

- Integrative Imaging (4) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Larval Olympiad (2) Apply Larval Olympiad filter

- MouseLight (18) Apply MouseLight filter

- NeuroSeq (1) Apply NeuroSeq filter

- ThalamoSeq (1) Apply ThalamoSeq filter

- Tool Translation Team (T3) (26) Apply Tool Translation Team (T3) filter

- Transcription Imaging (45) Apply Transcription Imaging filter

Publication Date

- 2025 (126) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (215) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (159) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (167) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (175) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (177) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (177) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (206) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (186) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (191) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (195) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (190) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (136) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (112) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (98) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (61) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (56) Apply 2009 filter

- 2008 (40) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (21) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (3) Apply 2006 filter

Type of Publication

- Remove Janelia filter Janelia

2691 Publications

Showing 2131-2140 of 2691 resultsDespite the importance of the insect nervous system for functional and developmental neuroscience, descriptions of insect brains have suffered from a lack of uniform nomenclature. Ambiguous definitions of brain regions and fiber bundles have contributed to the variation of names used to describe the same structure. The lack of clearly determined neuropil boundaries has made it difficult to document precise locations of neuronal projections for connectomics study. To address such issues, a consortium of neurobiologists studying arthropod brains, the Insect Brain Name Working Group, has established the present hierarchical nomenclature system, using the brain of Drosophila melanogaster as the reference framework, while taking the brains of other taxa into careful consideration for maximum consistency and expandability. The following summarizes the consortium’s nomenclature system and highlights examples of existing ambiguities and remedies for them. This nomenclature is intended to serve as a standard of reference for the study of the brain of Drosophila and other insects.

A number of recent studies have provided compelling demonstrations that both mice and rats can be trained to perform a variety of behavioral tasks while restrained by mechanical elements mounted to the skull. The independent development of this technique by a number of laboratories has led to diverse solutions. We found that these solutions often used expensive materials and impeded future development and modification in the absence of engineering support. In order to address these issues, here we report on the development of a flexible single hardware design for electrophysiology and imaging both in brain tissue in vitro. Our hardware facilitates the rapid conversion of a single preparation between physiology and imaging system and the conversion of a given system between preparations. In addition, our use of rapid prototyping machines ("3D printers") allows for the deployment of new designs within a day. Here, we present specifications for design and manufacturing as well as some data from our lab demonstrating the suitability of the design for physiology in behaving animals and imaging in vitro and in vivo.

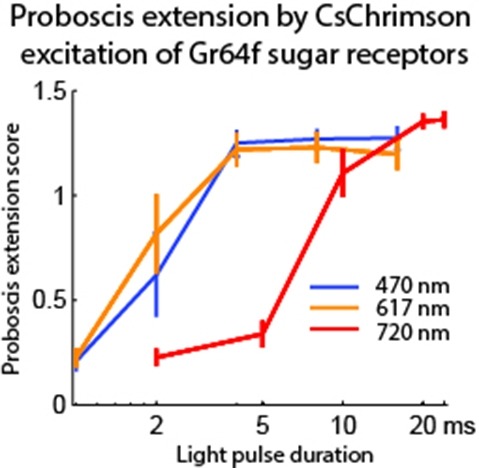

Optogenetic tools enable examination of how specific cell types contribute to brain circuit functions. A long-standing question is whether it is possible to independently activate two distinct neural populations in mammalian brain tissue. Such a capability would enable the study of how different synapses or pathways interact to encode information in the brain. Here we describe two channelrhodopsins, Chronos and Chrimson, discovered through sequencing and physiological characterization of opsins from over 100 species of alga. Chrimson’s excitation spectrum is red shifted by 45 nm relative to previous channelrhodopsins and can enable experiments in which red light is preferred. We show minimal visual system-mediated behavioral interference when using Chrimson in neurobehavioral studies in Drosophila melanogaster. Chronos has faster kinetics than previous channelrhodopsins yet is effectively more light sensitive. Together these two reagents enable two-color activation of neural spiking and downstream synaptic transmission in independent neural populations without detectable cross-talk in mouse brain slice.

We describe a method for fully automated detection of chemical synapses in serial electron microscopy images with highly anisotropic axial and lateral resolution, such as images taken on transmission electron microscopes. Our pipeline starts from classification of the pixels based on 3D pixel features, which is followed by segmentation with an Ising model MRF and another classification step, based on object-level features. Classifiers are learned on sparse user labels; a fully annotated data subvolume is not required for training. The algorithm was validated on a set of 238 synapses in 20 serial 7197×7351 pixel images (4.5×4.5×45 nm resolution) of mouse visual cortex, manually labeled by three independent human annotators and additionally re-verified by an expert neuroscientist. The error rate of the algorithm (12% false negative, 7% false positive detections) is better than state-of-the-art, even though, unlike the state-of-the-art method, our algorithm does not require a prior segmentation of the image volume into cells. The software is based on the ilastik learning and segmentation toolkit and the vigra image processing library and is freely available on our website, along with the test data and gold standard annotations (http://www.ilastik.org/synapse-detection/sstem).

View Publication PageHistone variant H2A.Z-containing nucleosomes exist at most eukaryotic promoters and play important roles in gene transcription and genome stability. The multisubunit nucleosome-remodeling enzyme complex SWR1, conserved from yeast to mammals, catalyzes the ATP-dependent replacement of histone H2A in canonical nucleosomes with H2A.Z. How SWR1 catalyzes the replacement reaction is largely unknown. Here, we determined the crystal structure of the N-terminal region (599-627) of the catalytic subunit Swr1, termed Swr1-Z domain, in complex with the H2A.Z-H2B dimer at 1.78 Å resolution. The Swr1-Z domain forms a 310 helix and an irregular chain. A conserved LxxLF motif in the Swr1-Z 310 helix specifically recognizes the αC helix of H2A.Z. Our results show that the Swr1-Z domain can deliver the H2A.Z-H2B dimer to the DNA-(H3-H4)2 tetrasome to form the nucleosome by a histone chaperone mechanism.

The organization of synaptic connectivity within a neuronal circuit is a prime determinant of circuit function. We performed a comprehensive fine-scale circuit mapping of hippocampal regions (CA3-CA1) using the newly developed synapse labeling method, mGRASP. This mapping revealed spatially nonuniform and clustered synaptic connectivity patterns. Furthermore, synaptic clustering was enhanced between groups of neurons that shared a similar developmental/migration time window, suggesting a mechanism for establishing the spatial structure of synaptic connectivity. Such connectivity patterns are thought to effectively engage active dendritic processing and storage mechanisms, thereby potentially enhancing neuronal feature selectivity.

BACKGROUND: Male-specific products of the fruitless (fru) gene control the development and function of neuronal circuits that underlie male-specific behaviors in Drosophila, including courtship. Alternative splicing generates at least three distinct Fru isoforms, each containing a different zinc-finger domain. Here, we examine the expression and function of each of these isoforms. RESULTS: We show that most fru(+) cells express all three isoforms, yet each isoform has a distinct function in the elaboration of sexually dimorphic circuitry and behavior. The strongest impairment in courtship behavior is observed in fru(C) mutants, which fail to copulate, lack sine song, and do not generate courtship song in the absence of visual stimuli. Cellular dimorphisms in the fru circuit are dependent on Fru(C) rather than other single Fru isoforms. Removal of Fru(C) from the neuronal classes vAB3 or aSP4 leads to cell-autonomous feminization of arborizations and loss of courtship in the dark. CONCLUSIONS: These data map specific aspects of courtship behavior to the level of single fru isoforms and fru(+) cell types-an important step toward elucidating the chain of causality from gene to circuit to behavior.

The placement of neuronal cell bodies relative to the neuropile differs among species and brain areas. Cell bodies can be either embedded as in mammalian cortex or segregated as in invertebrates and some other vertebrate brain areas. Why are there such different arrangements? Here we suggest that the observed arrangements may simply be a reflection of wiring economy, a general principle that tends to reduce the total volume of the neuropile and hence the volume of the inclusions in it. Specifically, we suggest that the choice of embedded versus segregated arrangement is determined by which neuronal component - the cell body or the neurite connecting the cell body to the arbor - has a smaller volume. Our quantitative predictions are in agreement with existing and new measurements.

View Publication PageThe quality of genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs) has improved dramatically in recent years, but high-performing ratiometric indicators are still rare. Here we describe a series of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based calcium biosensors with a reduced number of calcium binding sites per sensor. These ’Twitch’ sensors are based on the C-terminal domain of Opsanus troponin C. Their FRET responses were optimized by a large-scale functional screen in bacterial colonies, refined by a secondary screen in rat hippocampal neuron cultures. We tested the in vivo performance of the most sensitive variants in the brain and lymph nodes of mice. The sensitivity of the Twitch sensors matched that of synthetic calcium dyes and allowed visualization of tonic action potential firing in neurons and high resolution functional tracking of T lymphocytes. Given their ratiometric readout, their brightness, large dynamic range and linear response properties, Twitch sensors represent versatile tools for neuroscience and immunology.

Transcription is an inherently stochastic, noisy, and multi-step process, in which fluctuations at every step can cause variations in RNA synthesis, and affect physiology and differentiation decisions in otherwise identical cells. However, it has been an experimental challenge to directly link the stochastic events at the promoter to transcript production. Here we established a fast fluorescence in situ hybridization (fastFISH) method that takes advantage of intrinsically unstructured nucleic acid sequences to achieve exceptionally fast rates of specific hybridization (\~{}10e7 M(-1)s(-1)), and allows deterministic detection of single nascent transcripts. Using a prototypical RNA polymerase, we demonstrated the use of fastFISH to measure the kinetic rates of promoter escape, elongation, and termination in one assay at the single-molecule level, at sub-second temporal resolution. The principles of fastFISH design can be used to study stochasticity in gene regulation, to select targets for gene silencing, and to design nucleic acid nanostructures. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.01775.001.